Touch tells us that it has the slightly rough warmth of Reguengos de Monsaraz blankets, the irregular porousness of clay pieces that rise from the pottery wheels, the fresh relief from the walls, whitewashed year after year, with white lime.

The latest tribute to Monte Velho and the Reguengos blankets, to clay and lime, elements that paint the Alentejo landscape, while telling the story of the traditions and artisans that embody them. This earthy analogy began in 2016, when the traditional Reguengos de Monsaraz blankets leapt from their looms to Monte Velho labels and communication media. These intricately patterned blankets have a long tale to tell, starting with the sheep. Merino wool, an indigenous breed in Portugal, has a unique quality, with features that are recognised all over the world. It is inspiring to hear Mizette Nielsen tell the story of how she helped save this art, back in 1976.

«I recovered this factory to maintain a tradition that is so important, with a rich history that is part of the Alentejo culture.»

These Alentejo blankets go back a hundred years and used to protect shepherds from the cold, whether out in the fields or at home, but today they are essentially decorative and act as a fundamental symbol of Alentejo.

Monte Velho communication now extends its tribute to clay and lime. As for the brand’s signature, it remains “O Alentejo”. Artisanal pottery is an art made from earth and fire that, thanks to the skilful hands of the potter, produces jugs and mugs, tiles and tankards, dishes and bowls, fired and glazed crockery. Each piece that leaves the oven inherits knowledge from Greco-Roman and Arab times, from populations that date back 12 thousand years, in the Neolithic age, when three inventions were discovered that brought us here: agriculture, ceramics and writing.

São Pedro do Corval is one of the principal pottery centres in Alentejo, recognised for the quality of its clay deposits and the diversity of its artisans. This is where we talked to Egídio Santos, a clay enthusiast since his childhood and representative of the fifth generation in his family business, resisting plastic, moulds and time.

«You can be much more creative with the wheel and every piece is different. There’s a margin for error that often makes each piece unique.»

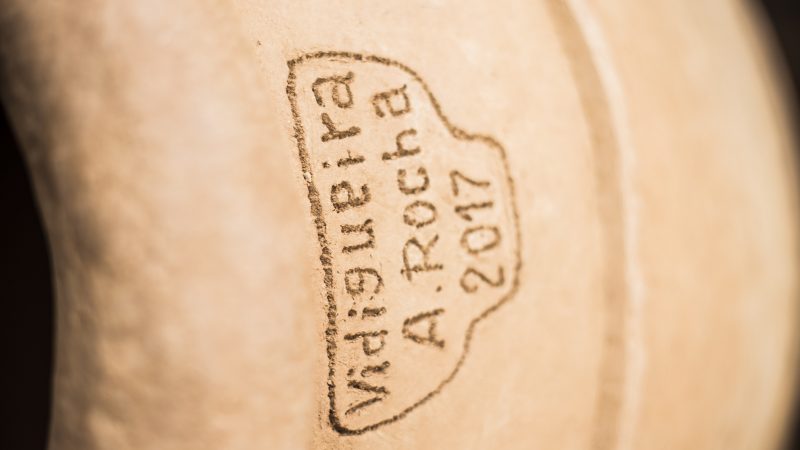

In another part of Alentejo, in Vidigueira, we found António Rocha, one of the few potters that specialises in producing amphorae, giant jugs (approximately 2 thousand litres) that the Romans used to make wine and which are also kept for decoration.

In Casas Novas de Mares we chatted with Felismina Ramalho, a seasonal painter who, paintbrush in hand, gave us a mini-workshop in the art of whitewashing.

«The lime comes in rocks and is melted in a bucket of cold water. We add rock by rock, because it will bubble and burn. We stir the lime to dissolve it well. Once it has dissolved, it is stored for 3 weeks before painting. It is even better for the lime to dissolve from one year to the next.»

White lime paints the Alentejo horizon, it is the wall’s flesh, a ritual of timeless gestures carried out by families. The lime, cooked in special ovens, is a symbol of renewal that, when thrown against the doorway attracts money to homes, a belief shared by the Alentejo people during the Middle Ages.

Like the hands that weave, shape and paint, the hands that craft

Monte Velho also respect Alentejo tradition. We dipped into the diversity of indigenous grape varieties, which originate from the four corners of Alentejo, and drew inspiration from the region’s vinification techniques to make a wine that could only come from this place: with rich aromas, a smooth palate and which pairs nicely with good food.

However, for the past 26 years the challenge to create a better wine has prevented us from producing two vintages that are exactly alike. It seems like a paradox but, to maintain the consistency of Monte Velho, an iconic wine that is consumed every day in more than 50 countries, it is impossible not to innovate. It is thanks to this healthy discontent that we now produce using entirely integrated production methods, a small step before achieving certified organic production.

If we close our eyes (as if to enjoy a good glass of wine) we can feel Alentejo in the warmth of the raw materials the earth provides, in the irregular porousness of the artisan’s hands and in the freshness of knowing that even tradition needs innovation.